This is a detailed guide on the idea of a visual path or journey that a viewer takes through your artwork. This is something I actively think about whenever I’m drawing or painting. I consider questions like: Where does the journey start? What direction is the viewer pulled? How do they work their way around the painting? What stops do they make along the way? What’s the end destination?

What’s the Goal?

The goal is to craft a visual path that invites the viewer in and guides them around the artwork, making a few stops along the way and eventually landing at the end destination (the focal point). And it should do so in a way that’s exciting and interesting.

There should be a sense of flow and interruption. That is, areas where the viewer’s eyes can move effortlessly through the artwork, then areas that interrupt that flow. This is how you add tension and drama. Areas that interrupt the flow are like exclamation points. They keep the viewer on their toes!

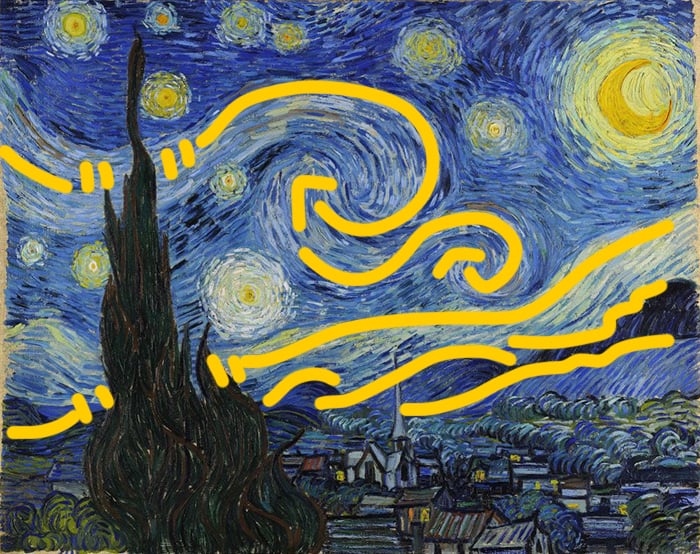

Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night is a classic example. Van Gogh takes our eyes on a visual journey through the landscape and sky with his swirling brushwork. Each area leads to the next and the journey is easy and pleasant. But then van Gogh smacks a big tree on the left-hand side, interrupting our journey and forcing us to pause for a moment before continuing. There’s flow and there’s interruption. That’s what you should think about when you’re creating your artwork.

You’ll see flow and interruption in good classical music. The piece will start with notes that follow a logical and predictable manner that’s pleasant on the ears. This will continue and gradually build up and up to a peak. But instead of hitting that peak note, it will play an off-note or a note that doesn’t quite get there. This interrupts the flow and catches you off guard. Only after sufficient drama and tension have been established will you finally get to hear that peak note around the end of the piece. Without this interruption, there would be no drama or tension. It might be pleasant at first, but you’ll grow bored. Benjamin Zander explains it well in this video:

Where’s the Focal Point?

You should design the visual path in a way that directs attention toward the focal point. Think of the focal point as the final destination for your viewer’s eyes.

In my painting, New Zealand, Foggy Mountains, the focal point is that faint waterfall in the distance. It’s not a strong focal point, but it’s a focal point nonetheless. Notice how your eyes are pulled into the painting with the upward strokes in the foreground. You are then led through and around the painting by the snaking stream and the lines created by the hills and mountains. Your eyes eventually arrive at the distant waterfall.

For artworks without a clear focal point, you might use the visual path to keep the viewer’s eyes moving from one area to the next. This is the case for my painting, Mount Tamborine (see below). I didn’t have a focal point in mind when I painted this. But I still considered the visual path and how I would move the viewer through and around the painting. The journey might look something like this: Your eyes first land on the dappled light and bursts of green in the bottom light left corner. You then move with the light across the path and then up the slope. You dance around here, then follow the light back across the path, around the greens, and up the tree. From the tree, you follow the light greens and yellows inwards toward the center… and so on. That’s that journey my eyes seem to take.

It Should Feel Unintrusive

The viewer doesn’t want to feel forced or pushed on a visual journey through your painting. They want to feel like it was their choice to go that way, even if it wasn’t. This means you should craft the visual path with a touch of finesse. Err on the side of subtlety and always make sure the visual path fits with the rest of the painting.

See my painting, Fiery Sunset, below. Look how I used the contours of the water to gently pull your attention towards the sunset. I didn’t need to do much as the sunset already commands so much attention. A faint zig-zag motion along the contours is more than enough.

Here’s another example, A Forest Stream by Peder Mønsted. At first glance, it doesn’t appear that Mønsted tried to push you in any particular direction or path. But look closely and you’ll notice the strategic patches of light illuminating the ground and creating a visual path for you to travel.

It’s best to use and manipulate what’s already there rather than trying to tack on a visual path to the subject. This will create a visual path that’s more natural and organic.

Ask yourself: How can I arrange the objects or frame the subject in a way that invites the viewer in, around, and through to the focal point? Can I use the grass at the bottom of a landscape to pull the viewer in? Is there a fallen tree that could connect one area to the next? Can I crop or adjust the composition in a way that makes for a stronger visual path?

Here’s another painting by Mønsted. Notice how the path and its shadows are strategically positioned so that you are led in and through the painting and towards the focal point (the horse and people).

Techniques for Creating Flow Along the Visual Path

Here are some techniques you can use to create and reiterate and move the viewer along the visual path in your artwork:

Visible and Directional Brushwork

Use your brushwork to push the viewer in the direction you want. You get extra points if that brushwork also plays into the nature of the subject. For example, in my painting, Maleny, White, Purple, and Blue Flowers, my brushwork at the bottom helps push the viewer’s eyes up and into the painting. The short, upward strokes also play into the idea of grass and flowers.

Lines

You could be more overt with your leading of the viewer’s eyes by using distinct lines. These could be outlines or contour lines, or lines that have no other purpose than to add a bit of flare and to lead the viewer around. Van Gogh did this in many of his paintings. It’s also an effective technique for drawing, particularly with pen and ink.

Pattern and Repetition

This is a more complex technique. Use pattern and repetition to lead the viewer along the path and to create a feeling of expectation. Think of it as a visual beat to the drum. It could be as simple as repeating the same shapes in a line. Or going light shape, dark shape, light shape, dark shape, and so on. Claude Monet did this with his Poplars series.

In Paul Sérusier’s Trees Along the Creek, see how it goes from light grass to dark tree to light grass and so on. This pattern draws your eyes along and creates flow.

Gradation

You could use some kind of gradation to lead the view from one area to the next. It might be a gradation in color, where one color melts into the next. Or it might be a gradual softening of your brushwork and edges. You’ll see this in most landscape paintings, where the colors might get cooler and less saturated as the objects recede into the distance. Edward Compton’s intricate landscapes are a great example, with the colors gradually getting cooler and weaker as everything recedes into the distance.

In my painting, Elora and White Roses, I used color gradation to draw your eyes through the grass. Notice how the colors are richer and darker around Elora and how they gradually get lighter and weaker as the grass tapers off in the distance.

Techniques for Interrupting That Flow

You can interrupt the flow of the visual path by doing anything unexpected or abrupt. It’s all about contrast. This might be in the form of a burst of color, dark accents, highlights, a solid shape, or an unusual pattern. Anything that interrupts the sense of flow and acts like an exclamation point. Below are a few different examples. I’ll leave it up to you to spot the areas of flow and the areas that interrupt the flow.

Eye Tracking

Technology exists that allows you to track the movement of the eyes through a screen. We can use this technology to track the visual journeys people take through an artwork. And if you get enough data, you can see what the path most traveled is. James Gurney has a few interesting posts on this. Links below:

James Gurney: Introduction to Eye Tracking Software

James Gurney: Eye Tracking and Composition Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3

An Exercise For You

The best way to learn this stuff is to put it into practice. So, before you start your next artwork, take a moment to consider the visual path and journey you want to take the viewer on.

Want to Learn More?

You might be interested in my Painting Academy course. I’ll walk you through the time-tested fundamentals of painting. It’s perfect for absolute beginner to intermediate painters.

Thanks for Reading!

I appreciate you taking the time to read this post and I hope you found it helpful. Feel free to share it with friends. Let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Happy painting!

Dan Scott

Draw Paint Academy

Thank you Dan,

This has helped me a lot – i create abstract and realistic work instinctively and I do these things naturally but you’ve helped me see how much further I can use this…

Krystyna

An enjoyment for my mind this description of techniques to guide the observer’s gaze on a pictorial scene and learn how other arts, such as music, use the same resource. I couldn’t help but see the similarity to the children’s story “The Pied Piper of Hammelin.” Thank you.

Outstanding post! I enjoy all your emails but this one is absolutely brilliant and the analogy to classical music just hits the right note. Thank you so much!

What a wild and generous and interesting post, Dan Scott!

Thank you very much. Now I want to read it again! xoxox

I learn something so beautiful and useable from each of your posts. Thankyou so much!

Thank you, Dan, for a very helpful post. I always enjoy your use of the masters and your own paintings to explain the techniques. I wish I had your looseness in my own attempts.

Look what I just found.. VERY excited…

Thank you, Dan! Excellent article and insight!

I’ve been meaning to comment for a while.

Your work and the articles you have been posting have just become better and better!

You must be reaching some kind of turning point in your life.

I am excited about what’s in store for you in the next chapter of your life!

Thank you for sharing!

Kert, in SE Wisconsin, USA

My reading of the eye tracking experiments is that that there is no “path” through a painting. You can pull a viewer’s eye by using faces and figures, and contrast, but you can’t get them to follow a “path.” I think the idea of a path may be useful for an artist in laying out their composition, but in practice there is no evidence that viewers see this way.

Thank you so much, great article, wonderful insights !!! You, made my day, I will now go and pull weeds, but think about all that you have taught me while I do so, and hopefully paint soon. Judith R. Legg

Absolutely love your generous and helpful posts, this is so good, I shall pay extra attention on my next painting. Hope your family are well, lovely the one with Elora and the Rose, thankyou again. Nicky Fernández.

As always, you are so generous with sharing your ideas. Thank you!

Agnes Daemen

Thanks Dan.

I have shared this on the Students of art Banburyshire UK FB Page.

It is so informative.

Thanks Dan, for sharing this information. My mind is swirling now at the thought of figuring this out for a painting! Wow! Do you do this figuring before you paint, as in creating a hook in a story? Maybe? I think this could be a subject for a long class! Thank you..I’m off to read it again.

You always hit right on the mark! Thank you very much.

Joan

Your words on art and learning are a constant source of mental stimulation and new appreciation of art in all forms. Thank you

I found this post an extremely helpful addition to my understanding of composition and I intend to put a number of the points highlighted into practice. Thank-you for sharing your expertise on this subject.

I am an utter beginner! But I think I can begin thinking this way even as I do “some simple” exercises. Thank you for all the examples! So helpful! And, yes, I do share your column with my other art friends!

Nancy

Danville Ca

I’ve heard of the idea of guiding viewers through an image but have never paid much attention to it. Your examples are impressive, they make me understand and appreciate the concept. I’m looking forward to new posts, thx.

Your examples truly impressed me; they helped me grasp and value the idea better. I am eagerly anticipating your upcoming posts.